I recently attended the Legal Design Summit in Helsinki, an event exploring the intersection of law, design, and technology. (The picture above from the presentation by Jenni Hakkarainen.)

Heikki Ilvessalo

Antti Innanen opened the summit with reflections on legal design in the age of AI, setting the stage for how design principles can influence legal work. At its core, legal design aims to make legal products and services—laws, policies, contracts, dispute resolution procedures—more user-friendly. When processes and documents are easier to understand, they are also easier to follow, which benefits individuals, businesses, and the wider legal system.

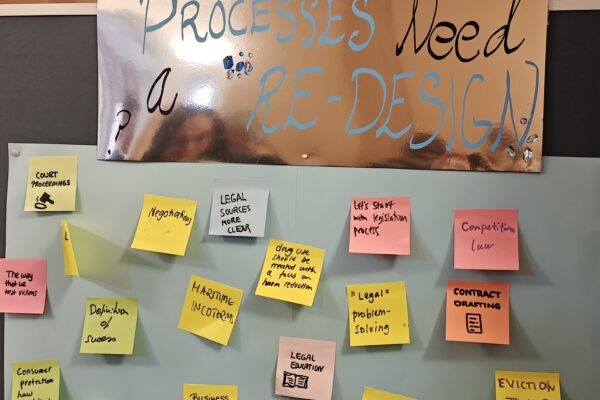

Outside the main lecture hall, participants were invited to contribute their thoughts on questions such as:

- Which legal processes need to be re-designed?

- Which topic will shape the future of law the most?

This interactive element underlined the collaborative spirit of the field.

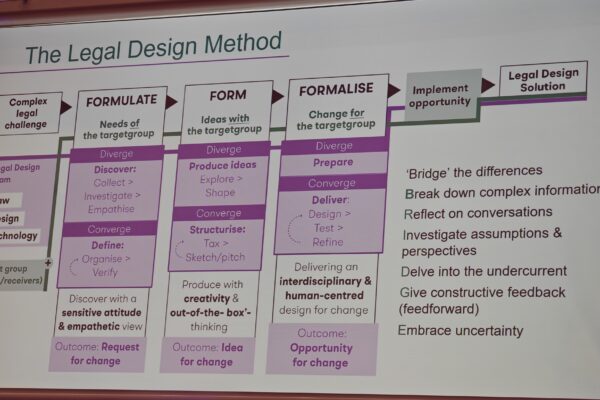

The legal design method was described as a structured approach to addressing complex legal challenges. It involves three stages: identifying the needs of the target group, co-creating ideas with them, and formalising those ideas into practical solutions that can be implemented.

Peter Hornsby illustrated how this can work in practice by focusing on the design of legal documents. The approach can range from narrowly reducing errors to broadly supporting an organisation in achieving its goals. Examples raised in discussions with delegates included more user-friendly versions of common documents such as NDAs and privacy policies (see Visual Contracts NDA and Juro Privacy Policy). But Legal Design has moved beyond documents and is also used to (re-)design legal services and organisations.

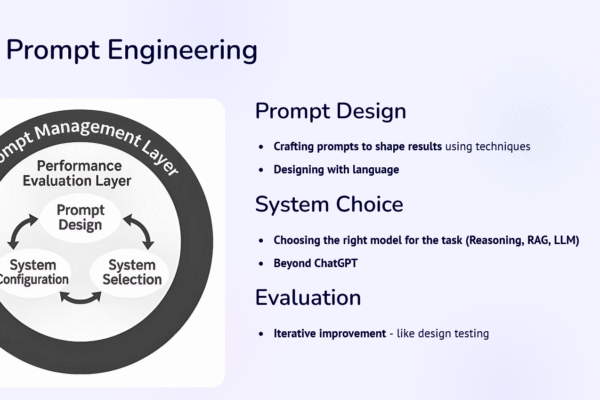

Christian Djeffal addressed legal prompt engineering, connecting it to design through theperspective of AI. He described it as a performance evaluation layer where prompt design, system choice, and feedback loops interact to improve outcomes.

In conversation, Marion Ehmann offered a practical way to understand legal design. In her workshops with law firms and legal departments, she frames it as an exercise in professional empathy. The focus is on questions such as: What are clients’ pain points when they engage with legal processes? Which problems do they need contracts to solve? What would make the experience easier or more engaging for them?

The summit offered some insights into what legal design can mean in practice. Using the established framework of Design Thinking/Doing (developed at Stanford Uniersity), it is a set of approaches for making law more accessible, responsive, and effective.